Pretty early on in his career Yonatan Stern understood that “there is an inherent conflict of interest between what the entrepreneur wants and what investors need”. So he developed a unique model to fund new companies, founded and sold three start-ups for a combined sum of over $1 B, and is now charging ahead with a new company – and fulfilling a dream along the way – Ruti Levy

In 1992, entrepreneur Yonatan Stern was running a startup that developed technology for troubleshooting complex systems, such as CT and MRI machines. The company, Rosh Intelligent Systems, was considered successful in tech market terms: it sold to large corporations such as Philips and Siemens, its revenues grew by 30% – 40% a year, and like many startups, the company worked on generating revenue and increasing its market share, at the expense of profitability.

However, Stern concluded that as CEO, he was spending too much time fundraising in order to support the company’s continued growth, rather than focusing on building and managing the company. He met with the Board and explained the need to reduce expenses and cut back on certain activities in order to bring the company to profitability. The Board, made up of venture capital investors, disagreed, and Stern decided to leave the startup he had founded.

“I realized then that there is an inherent conflict of interest between what the entrepreneur wants and what investors need,” he said. He continued, “If a company is not large enough to list on the stock exchange, and no one buys it, they’re stuck. These companies’ business model is based on raising money with ROI repayment within 7-10 years. This creates pressure on the entrepreneur to promote faster growth, since making an exit from $10 million of revenue is irrelevant, but a revenue of $100 million is relevant.

“But what does the entrepreneur want? Most of us are not looking to make money from money; we want to build something sustainable, like Gil Shwed did with Check Point, build a product and technology, walk into the office and see 50 people at work. At that Board meeting, I told myself – from now on, I will build companies that will be profitable, and everyone will know it.”

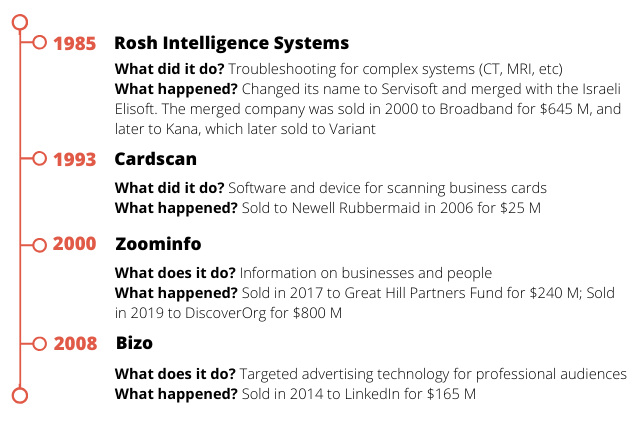

Since that decision, and for two-and-a half decades, Stern (65) set up profitable companies almost from the start, with minor or no investments at all – and sold them for tens and hundreds of millions of dollars to companies such as LinkedIn and the US consumer consortium Newell Brands. Two months ago, he registered another impressive feat when he sold his creation ZoomInfo to his greatest competitor DiscoverOrg for $800 million – three times the value for which part of it was sold only two years earlier to the Great Hill Partners fund. Despite all this, over the years, Stern has maintained his anonymity among the Israeli public, and this is his first interview to the press.

Already a computer teacher in high school

Stern studied at the religious Himmelfarb High School in Jerusalem, and was first exposed to the computer world thanks to his math teacher, Moshe Nordheim. For a while, Nordheim arranged for his students to have access to the large computer at the Hebrew University and taught them Fortran programming (used for scientific applications even today). At that time, programs were written on paper, punched into cards and transferred to the computer which produced a perforated output. When the students were kicked out of Hebrew University, Lev College loaned them their computer in return for use of the school’s campus in the afternoon, and Stern was charged with supervising it.

The turning point occurred when Nordheim left to work as a programmer at the National Health Insurance, and Stern, a senior in high school, became the computer teacher. Stern enjoyed teaching and hoped to become a university professor in the future, but also realized very early on that he deserved compensation for his work, and therefore went to the principal and demanded a salary. “The principal, Abraham Goldberg, a highly-respected man, said: ‘Yonatan, but you enjoy it.’ I answered, ‘Wait, you only get a salary when you suffer? Don’t you enjoy being a principal?’ So he asked how much I wanted,” he recalls.

After high school, Stern turned to computer science studies as a soldier-student at the Technion. At the end of his studies, he joined the 8200 unit, and served in the same unit where Shwed and Shlomo Kramer later served. During his military career, he completed his Master’s Degree in Computer Science and had already planned his postgraduate doctoral studies after his release when his friends convinced him that he should “go into business”.

The most important answer in business

Stern founded Rosh Intelligent Systems together with friends in 1985, years before the government’s “Initiative” program was created, giving birth to the local venture capital industry. At the time, only one company invested in local high-tech, Uzia Galil’s Elron Company, and a new venture capital fund called Athena set up by former Air Force Commander Dan Tolkowsky and the American venture capitalist Frederick Adler. From both he raised $11 million for his company Rosh Intelligent Systems.

In the 1980s, Israeli high-tech had two flagship companies – Elscint and Scitex – both valued at $100 million. Discussions in the media at the time, Stern says, centered on the question “Why can’t Israel create billion-dollar companies”. “Journalists asked, ‘What prevents Israelis from reaching one billion dollars?’ I quickly realized that what was missing was time. An entrepreneur wanting to build a successful and sustainable company, who makes no pretense of wanting to solve the world’s problems, doesn’t have to rush to raise capital,” says Stern.

He learned the most important lesson from personal experience. In the years during which he created Rosh Intelligent Systems, he watched another company climb and become profitable very quickly. This company developed CRM systems (Customer Management) and its product was widely used among those businesses Stern identified as potential customers for Rosh Intelligent Systems (Rosh).

“I went to the customers and said, ‘I don’t understand, why are you throwing so much money at their product, but nothing in my direction?’ One customer told me, ‘Listen, my technicians have spare parts worth $50 million, only I have no idea which technician holds which part. With this system I know where everything is, and when someone wants a spare part all he has to do is send a request and we can tell him that the technician who has the part he wants is only 2 km away from him.’

“I listened to this and said dammit – I solved a much bigger problem with complex technologies, but they solved a problem that can be quantified. That was a life lesson. Since then I always ask customers, ‘If you have $100 to invest in any product, will you buy my product or spend it on something else?’ When you ask this question, you get answers you don’t like to hear, but they are the most important answers in business.”

You don’t need to be the first, but you should be the best

When he left Rosh, Stern decided to start a new company and searched for “a product that anyone who sees it immediately understands what it does.” This product was a small business card scanner that connects to the computer and transmits all the information scanned from the cards directly to it. That was in 1993, when the Internet was still in its infancy. Stern decided he needed to collect the technologies needed to develop the product, and called OCR companies (Optical Character Recognition technology). When he explained why he wanted the technology, they told him to stand in line. It turned out there were ten other companies doing exactly the same – but that didn’t stop him.

That same year, Stern attended the Comdex Conference in Las Vegas, in those days the biggest computer exhibition ever, owned by the American billionaire and now owner of “Israel Hayom,” Sheldon Adelson. “I was just getting started, and one of the competitors had already come out with a product. I picked up the phone and called Dexter, the developer who worked with me. I told him we had a problem, we won’t be the first anymore, and he simply answered, ‘If we’re not the first – we’ll be the best’”.

There’s always talk about being the first, about market share, and putting a product out on the market when it’s “good enough”.

Stern says, “That’s not true. The first ones almost always die, because it takes time to really understand what the market wants. Hundreds of social networks existed before Facebook, and billions were thrown into this market. MySpace was sold for a fortune at the time, a whopping $580 million, and evaporated. Why did they all fail and Facebook succeeded?”

Why?

“Because when you signed up to MySpace, they, of course, stole your entire address book and informed all your friends that you were on MySpace, and the next day you were happy to have some friends there; you corresponded with them a bit, but a week later there was nothing for you to do on that network. Only one smart person, Mark Zuckerberg, said, ‘I’ll give you a reason to stay’, and turned Facebook into a media company – where everything you do is broadcast to the world, just like the news.”

At that time, Stern lived in Boston, Massachusetts, where he had moved to manage the Rosh computer systems from the company’s headquarters, and stayed while his wife completed her doctorate program. He called the new startup CardScan, and over the years raised $4 million from three American venture funds – Ascent, Flagship and Commonwealth Capital. In the late 1990s, CardScan was a small, profitable company, selling its product for $250 to resellers like Office Depot. When the world began to talk about the Internet, Stern was often asked about his “internet strategy,” and thus, he says, he “began to look at what was happening on the internet.”

When he looked, Stern found that the information on search engines was limited. If, for example, you want to pull out a list of software companies in Boston, and no one has collected and uploaded that information online, the information is not available. He became interested in developing a search engine that reads all information online and extracts it into databases. This was the start of ZoomInfo, which later became a company with an updated database of more than 100 million contacts from various business fields around the world.

ZoomInfo was established in 2000 with two engineers and one salesman that had worked at CardScan. Once it had acquired the basic technology, Stern informed investors that he wanted to start a new company (Spin-Off) and finance it through a loan from the existing company. He would continue to reproduce this model in the future with Bizo which, born as a spin-off of ZoomInfo, developed advertising technology targeting business professionals.

When you’re asked if it can be ‘better,’ you get good ideas

The basic idea behind ZoomInfo was to take Internet information and make it accessible for business purposes. In the first decade of its existence, its clients were in human resources. This was before LinkedIn became popular, and companies had no way of locating candidates who didn’t send them resumes (passive candidates) – headhunters (professional recruiters) would buy this data.

However in 2009, Zoominfo realized that there was a bigger market, for business sales. Its new clients were B2B companies – those who sell their services to businesses – and the question that interested ZoomInfo was how to create lists of potential customers for them based on data insights. “We built the database to allow you to filter your searches based on characteristics indicating that the company might be interested in your product. The rationale is that the closer you go from a random list of potential customers to a list of customers requiring a company’s solution, the more your information is worth. Because, if you are a business, you will pay 10 cents for a name and address, but $100 for a company that’s going to buy a product like yours,” Stern explains.

“Therefore, as an experienced salesperson, your customers give you indications of what kind of products they need; for example, your system will be appropriate for companies with more than ten salespeople who already use a CRM system and marketing automation. If you filter our database according to these parameters, you’ll reach the most relevant customer list. From our side, in order to be relevant to different markets, we had to learn about them so we could add more filtering options.”

Stern tells us that as of 2012, ZoomInfo’s yearly revenue and profits began to grow from year to year at a high rate. “It happened thanks to the question ‘Can we do better than that?’ For example, a salesperson came to me one day and told me, listen, I discovered a new market – transport. Imagine there’s a transport company and five trucks. Who do they work with? They work for other companies. They transport from warehouses to parking lots, from the warehouse to the manufacturing plant. Transport companies work for businesses that also require a database. Two salespeople developed a new market for ZoomInfo that resulted in very large sales. So I learned that if you ask people ‘Can you do better,’ you get both delusional answers and good ideas.”

ZoomInfo currently employs 50 people in Ra’anana. Most of its shares were sold to the Great Hill Partners fund in 2017 at a value of $240 million, and Stern continued to serve as CEO. Less than two years later, in February 2019, the company tripled its value when it was sold in its entirety to the American DiscoverOrg for $800 million. According to Stern, most employees enjoyed the sale twice since he made sure to refresh their options as part of the deal with Great Hill. Another condition Stern insisted on maintaining during the first sale of ZoomInfo is the profit-sharing mechanism he built at the outset – according to which 20% of the company’s earnings are distributed to employees regularly every quarter. ZoomInfo’s profit, according to estimates, was 40% of its revenue, which was valued at tens of millions of dollars. Stern states that between 2017 and 2018, the company’s revenues increased by 90%. He believes it will double its revenue in 2019. “I have no doubt that the company will be listed on the stock exchange in a year or two, and the price that DiscoverOrg paid for the deal will seem ridiculous,” he says.

What do employees really want?

ZoomInfo does not hold ceremonies for outstanding employees and annual assessments. Stern also does not believe in promising prizes alongside business goals – “It feels like a bribe.” In his opinion, executives should give employees an unexpected boost; for that reason, he created a reward called ‘Night in Town.’ “If someone does good work, the boss calls him over quietly, says ‘well done’ and gives him a certificate that says ‘Go to the best restaurant in town, have fun, and bring us a receipt.’ We give the employee up to $250 to be used within two weeks in order for it to have the right effect. The spouse should also be the one to go out with the employee, because it shows the spouse that the employee is appreciated, and that there is a reward for hard work. Every manager has the right to do this. We distribute about ten vouchers a month in a company of 150 people,” he says.

According to Stern, the most important thing he learned over the years regarding employee management is that employees want attention and recognition. “Recognition means that the boss calls you into the room and says: ‘The article you wrote is amazing, I would only change a few things.’ The employee then realizes that the boss read, responded, and paid attention. If he does this randomly twice a month, the employee will say, “Good, he knows what I’m doing; I want to work with him’.”

“Praise and attention is not given publicly but rather in private, because the person who receives it will forget it a day later, and the one who didn’t will remember it his entire life. People also want constant, not sporadic, attention. I ask my managers to go over each and every employee separately and tell me what they’re each working on. If they can’t answer, I tell them ‘What kind of managers are you? Haven’t you sat with the person this week?’.

The money he raised ‘by mistake’ and the new company

Over the years, Stern relied on the same modest $4 million investment that set his first company on its feet, and enabled the establishment of the two companies that followed. The original CardScan shareholders continued with him from 1993 at the same holding rates they had for the last three companies, that sold for a combined sum of over $1 billion. Employees who helped him develop any new startup were listed as founders. However, there was also the time he raised money “by mistake”.

“In 2004, when I was about to return to Israel, Mike Tyrell, an investor from the Venrock Fund (one of the biggest investors in the US), came to me and said ‘I’m going to invest in you.’ I said I didn’t need it, but he insisted. He came to my office every week. In the end, I told him I would explain why I didn’t want him to invest.”

“First, I said, in a few months I’m going back to Israel and you don’t want to invest in a company whose CEO has moved to a hole in the Middle East. He answered that he is very active in Israel (Venrock, among others, has invested in Check Point; RL). Secondly, I said I did not want to lose control of the company, to which he replied that he could handle that as well. In the end, he invested $6 million in the company, money we never used because ZoomInfo’s profits from very early on were able to fund the company’s growth. However, it was an investment, and as a shareholder he made a lot of money from ZoomInfo, and from Bizo which spun off from it.”

Although Stern spent most of his entrepreneurial life in the United States, he believes that local entrepreneurs should reside in Israel. “You can sit in the country and feel as if you’re abroad; the phone has an American number, the sale process is entirely virtual, you can share screens remotely, transfer files, and chat on video. Also, customers don’t really want to see you – because if you come to their office it takes up an hour of their time, but if you make a phone call the whole thing is over in ten minutes, and they can compare you to competitors.” He also said it was easier to recruit employees in Israel: “Everyone knows everyone and they bring their friends, and there’s a lot of talent here.”

As far as marketing and sales positions are concerned, the recommendation is to keep them near their market and recruit Americans.

“Apparently my way of thinking differs from everyone else’s. My Marketing VP is an Israeli, she’s a mother of three, and you have to see her results. I have nothing against Americans, but I don’t think that the fact that they learned how to be polished way back in preschool gives them a relative advantage, given that you often find out what you bought is just a brochure. The first time you say ‘Wow, what a presentation,’ and then you hear him repeat the same thing at every meeting.”

Today Stern spends most of his time working on a dream he developed in High School – applied research. He’s doing this with his fifth company, the ‘Yonatan Institute.’ “In each of my companies, the basic algorithms and technology were elements I developed myself. But because ZoomInfo is an economic company, I often cut corners – if a problem had to be solved, I strived for the fastest possible solution,” he explains. Stern is engaged in facing new challenges in the field of understanding language. While working with ZoomInfo, he noticed that much of the information we collect on the Internet is not given in natural language, but deciphered out of context. “If you go to a company website and want to know who the CEO is, you go to ‘About’ and ‘Management’, where you will see a picture of the CEO. You will not necessarily have a full sentence in English telling you this is Yonatan Stern and he is the CEO of the company.” Stern is trying to build a system that can be taught to extract meaning on its own. “I was planning on being a professor, and that didn’t end up happening, but I still have that bug. The result will probably be another startup.”